Sweet Shaman Heart: Sufi-infused Magical Cults, Ethiopian Influence, & Djinn on the Persian Screen

The winds refer to mysterious, ethereal and magical forces which can be anywhere... Where there is fear and anxiety, the winds blow. -Under The Shadow (2016)

What I admire most about Under The Shadow1, a Persian film (modern-day Iran=Persia) isn’t necessarily that it was shot in Jordan—you’d have a hell of a time trying to film a movie in present-day Iran—or that it so brilliantly displays one 80s Persian family’s ebb and flow amidst the Iran-Iraq war that rages around them—or even that the film falls neatly into the horror genre.

No.

What I admire most is that the film acknowledges that wherever fear and anxiety blossom, djinn abound.

Loose parallels for the culturally Christian: Islam has djinn, Judaism has dybbuk, and Christianity has demons.

(I am not an Abrahamic scholar, I just come from Abrahamic tradition and gravitate toward one of its branches specifically)

Now, djinn (pronounced gin in both the singular and plural in English), aren’t inherently evil. Djinn, as far as I can see (I’m pulling all of this information from a book called Shamanism and Islam, edited by a one Zarcone and Hobart), equate to the idea of a non-human, sentient spirit in Islamic thought.

There can be good djinn and there can be bad djinn.

In any case, djinn go by different names—and are, at least sometimes, referred to as winds or as people of the air in Iran.

In Under The Shadow, the djinn definitely aren’t good and they definitely take flight—they land on this unwitting Persian family from above:

The city where this family lives—Tehran—is constantly and randomly bombed by Iraqi missiles throughout the movie—bombarded with anxiety and uncertainty—the djinn are able to hitch a ride on an Iraqi missile that later careens into their Irani apartment building.

In the film, it’s the wife and mother, Shideh, who first postulates that djinn are present, like an airborne sickness, in her home. Her daughter, Dorsa, has begun acting strangely, stressing about djinn—worrying that they’ll kidnap her precious doll, Kimia, a gift from her dear father: a doctor involuntarily drafted to fight against Iraqi forces. This drafting boots him from the screen early in the movie, leaving Dorsa and Shideh alone and vulnerable.

While the father is away, a more traditional and nosy neighbor with small children must adopt her husband’s distant nephew into their home—his parents having been killed in a missile attack in another city. The nephew is 9 or 10, healthy, strong, and mute. Yet Dorsa is adamant that he has whispered warnings of djinn to her while playing together. The nosy woman (pictured left) enforces this idea of the presence of djinn.

Shideh asks a different, learned neighbor (above on the right) about a book (The People of the Air by Ghulam Husayn Sa’idi) that they’re both aware of. It’s an anthropological text that explores sufi-shamanistic practices that exist in southern Iran to expel, or at least control, the hold of evil djinn on people.

I think of Sufism as the intellectual, mystical side of Islam—so it makes sense that this open-minded circuit in the faith would allow space for exotic, shamanistic thought to survive in a monotheistic ecosystem.

The book is not a place to look for answers to life’s questions, according to Shideh’s learned neighbor. It’s, supposedly, a text on wind superstitions—on djinn.

Well, Sa’idi’s name, when it floated out from the speakers of my projector, stuck in my mind. Shideh reads aloud his Persian text:

“The winds refer to mysterious,

ethereal and magical forces

which can be anywhere...

Where there is fear and anxiety,

the winds blow.”

Anxiety: The Puffer Fish You Love to Hate

Now, fear and anxiety, for me, have been the great torment of my mind this past year. I think of anxiety as an unhelpful puffer fish in my chest with no other purpose but to expand and prick my heart into palpitations:

In my pursuit to understand myself and my anxiety, I saw Under The Shadow, and began to search for Sa’idi.

What could he tell me about djinn and their hold on me in my anxious states?

(I think of djinn, demons, dybbuk, and angels—puffer fish—as all serving a symbolic purpose to help visualize and name toxicity and evil—and goodness—in our day-to-day, at the same time that I believe they are very real and, when I suffer from something, I research it until I feel I know everything about it. This is to destroy it, or at least control it)

I believe that the more you know about what ails you, the less it ails you.

The obstacle with Sa’idi is that he is a little-known scholar now and wrote in Persian (Farsi)—Under The Shadow is a Persian language film.

I neither speak nor read Persian and have been unable to find his works translated into Spanish, English, or Portuguese—that was until I finally came across Shamanism and Islam where one thorough, thoughtful scholar, Pedram Khosronejad, translates an entire chapter of Sa’idi’s book. Through Khosronejad I reached Sa’idi, and what I learned was fascinating—also Khosronejad is easy on the eyes. Check him:

The Ethiopian Presence in Iranian Islamic Culture

What I had known about Ethiopia before reading Sa’idi’s translated chapter was little more than the existence of a gifted, Ethiopian funk musician, Mahmoud Ahmed, and Ethiopian sponge bread that I tried in 2019.

What I learned about shamanism in Iran, in regards to expelling djinn, is that it isn’t something that Islamic religious authorities feel is kosher—to borrow a term from Judaism. That’s to say that if you’re Muslim and you feel you have a djinn infestation there is no official religious authority you can call to quell it (that I’m aware of).

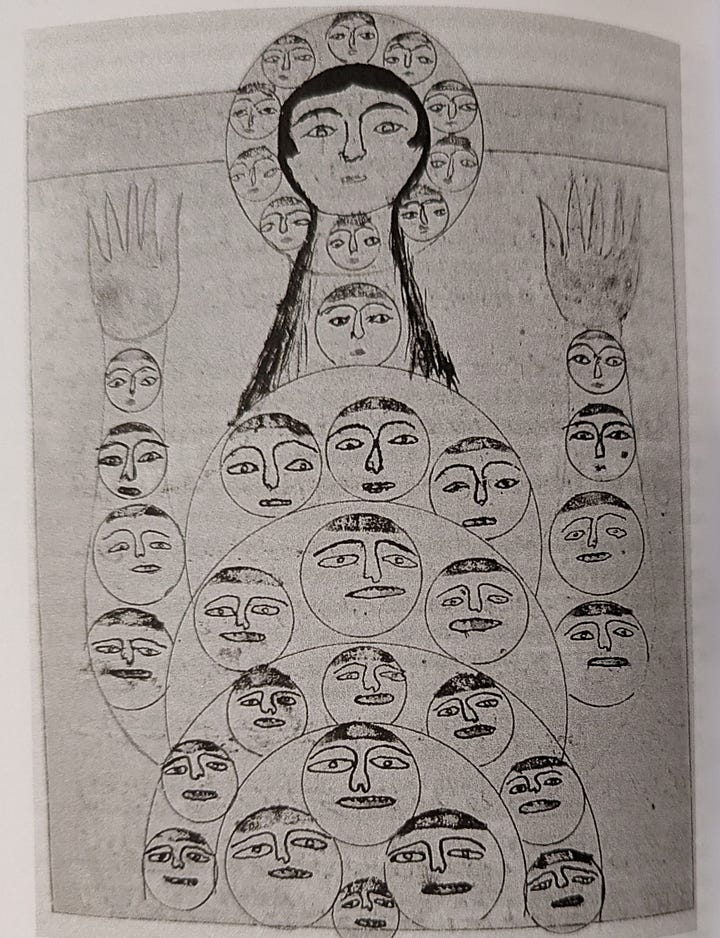

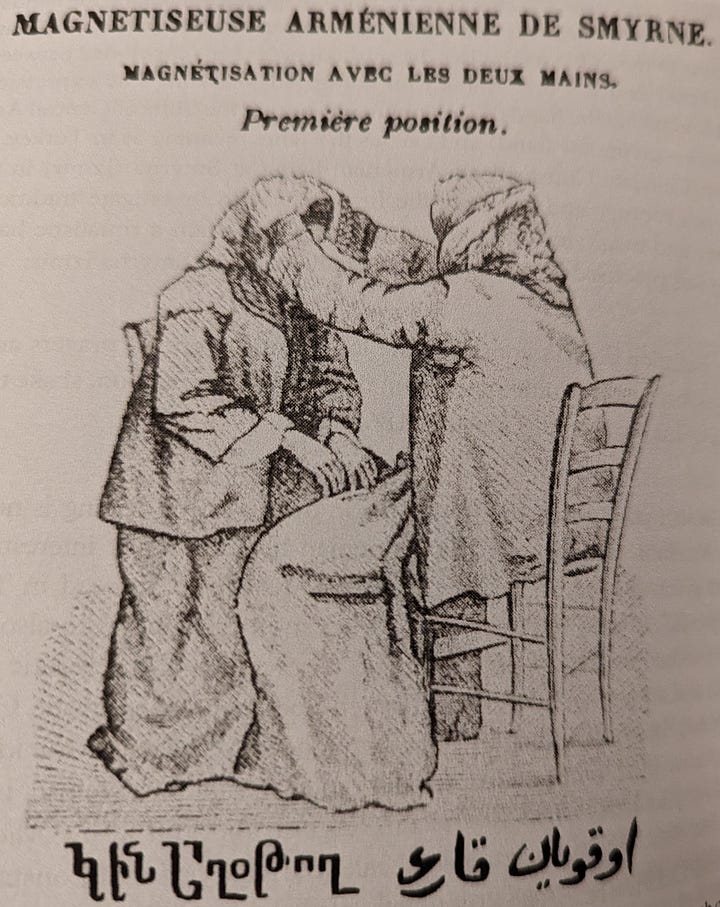

However, there are, according to Khosronejad’s translation, cults (not sects but simply magical/religious groups in this case) that can be consulted because they exist to detach djinn from their victims. In the context of the film, and of Iran, these cults are sometimes called zar.

In most regions of Iran where zar is found, the cult is basically a woman’s religious activity, considered unorthodox and as such often criticized and ridiculed by men and the educated. 2

In Khosronejad’s research, he finds that it’s most likely a tradition with roots in—guess.

Ethiopia: northern Ethiopia to be exact.

Well, damn—how the hell did this east African practice get to southern Iran?

You can ask the same question about how numerous African traditions came to the United States.

The answer is slavery.

There was a slave-trade between northern Ethiopia and Iran at one point, and djinn traveled with the enslaved to Iran, theoretically speaking.

Therefore, it is black women in southern Iran that, if they still exist, are the most respected and efficient zar cult leaders. They call themselves zar—exactly what these evil djinn are referred to as: zar.

Zar fighting zar.

According to these black women leaders, it’s well-known that evil zar spirits attack socio-economically vulnerable people in certain geographic areas (particularly near water).

Their attachment to people is tortuous and disrupts daily life.

The other point brought up in Islam and Shamanism is that, anthropologically speaking, possession by djinn, in a medical sense, is a psycho-active, physical, psychological manner of communicating—on behalf of the possessed—a need for social inclusion or social change.

Let’s say that a disenfranchised black woman in southern Iran lives an ostracized, impoverished life. She sticks to her oppressive social circuit—or lack of social interaction—until she no longer can abide the hardship. She then begins to display signs of a possessed person: fits, personality changes, violent behavior, seizures, outbursts, etc.. She begins to cause a commotion in the social sphere of her culture.

She begins inserting herself where her peers feel she does not belong.

She becomes so loud that the people around her must address her and her needs—her need to be healed, perhaps—or included, respected, or acknowledged. Through her possession, she’s able to reenter society and play a role preferable to pariah.

You can grasp the idea of how possession or attacks by djinn are reflecting anxiety, fear, and hardship—perhaps they’re even manifestations of societal toxicity.

Naturally, we can see how dropping Sa’idi’s name around this particular subject tips us off to the fact that the creators of Under The Shadow are making a statement about Irani culture and context: there is something toxic in war, in the bombing of nations, in the environment that Shideh experiences in Iran in the 80s.

(She’s blocked from attending medical school for her “liberal” political beliefs prior to the Irani Islamic Revolution—today, February 11th, is Iran’s Islamic Revolution Day by the way. Depending on who you are and what your relationship to Islam in Iran is, this is nothing to celebrate)

It’s only when Shideh is able to uncover superstitious, quasi-islamic sufi-solutions to her djinn infestation that she may escape her supernatural affliction.

Perhaps this is a subtle filmic suggestion that the Irani government requires a bit more open-mindedness in their interpretation of Islam if they want to expel their demons.

OG The Djinn Magnet: Anxious and Strong

According to Sa’idi’s research, evil zar (evil winds, i.e. djinn) prefer to attack—not the weak—but the strong:

“…a wind loves young and strong targets as they possess a great amount of energy”

You may ask, dog, what are your conclusions from all of this reading, watching, and thinking?

YO, IT’S NOT THE WEAK, BROTHERS, THAT ARE PLAGUED BY INTERNAL TURMOIL AND ANXIETY, IT IS THE STRONG. I AM STRONG. THESE MFS WANT ME FOR MY ENERGY.

Through this film and through Sa’idi, I learned a bunch more about shamanism and Islam around the world, too:

During Islam’s come-up the fiddle was seen as the devil’s instrument. You can get pretty wild with a fiddle—ngl.

Fatima (the Prophet’s daughter) was speculated to be the first shaman3.

Sufi-shamans can sometimes heal you by transferring your ailment to another person or object. Herpes is an example in the book—a healer transfers the virus from one person to a sponge.

There might be a mother-of-jinns figure called Shehret ul-Nahr—can't find much on her, expound if you can.

Definitely watch the film, maybe read the book—listen to Mahmoud Ahmed for sure—and next time you beat the fuck out of yourself for succumbing to anxiety or fear, perhaps adopt the thought that you’re strong and are seen as strong by entities who envy your strength.

Perhaps they see your strength as a precious resource in this world and the next, my sweetheart reader—my sweet-shaman-heart reader.

All images are used for educational purposes here and in any of my Substack work, please forgive how poorly referenced they are.

You can find this quote on page 149 of Shamanism and Islam.

195 of Shamanism and Islam but a different chapter “Shamanism in Turkey: Bards, Masters of the Jinns, and Healers”